|

|

|

|

Ugly Paris Buildings |

||

|

The Dark Side of the City of Light I know the beauty of Paris as well as anyone. I have basked in its glow, been inspired by it, written, and dreamt about it. I am not alone. People flock there by the millions every year riding on the myth of this the most beautiful city in the world. And few are disappointed. As long as they stay in the center of the city that is. Venture a short distance outside the center into the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th arrondisements and things change radically. Everything we think of as being Paris disappears as a grim urbanism takes over. Go further yet into the suburbs and one is submerged in the most drab and dismal of urban landscapes. The truth is there are two Paris’s. Central Paris, the Paris of the postcards where all the tourists congregate and swoon, and the Paris of the outer arrondisements where tourists never tread. All it takes is staying on the Métro a few more stops to leave central Paris. Within minutes one passes through an invisible veil from a wondrous dream into a cold shower of reality. It wasn’t always like that. Until the 1960s there was a consistency and continuity as one moved from the center of Paris toward the edge of the city and beyond. The center, of course, was always more dense, more plugged in, had more happening, and the further one went towards the edge of the city, less so. The consistency, however, was in the feel of things. Everything one encountered felt part of the same world. Be it picturesque, scenic, or even uninteresting, there was a continuity to it all. Then somewhere in the 1960s an urbanism on steroids hit the scene. A drive into Paris from the airport spells it out clearly. The architecture of alienation spills across the landscape like a B Hollywood horror movie. The center of Paris has been spared this fate, but only by a hair. Few people know that in the late 1950s, the Marais, one of the most cherished and expensive quarters of Paris today was so dilapidated that it was tagged a slum and slated for demolition. Fortunately a small group of enlightened minds came together and saved the Marais not only for Paris but for the world.* Another example is on the corner of Rue Barbette and Rue Elzévir. But the winner is on Rue Beaubourg at the corner of Rue Saint-Merri. See the photos here. Buildings as mediocre as these would go unnoticed in America and simply fade into a wash of greater mediocrity. But here in Paris, in the Marais, in the middle of a quarter known around the world for its architectural beauty! In the arrondisements beyond the center of the city the tipping point has been reached and one is in for a shock. In those Parisian quarters large scale urban renewal projects have erased whole neighborhoods in the Haussmann style of urban clear-cutting but without any of the visual interest of his work. And unlike the disaster of Les Halles, the old central market torn down in the 1970s and replaced with a misconceived garden and an underground shopping center, and today slated for demolition and grand redesign, these urban renewal projects and their blight are here to stay. For other examples see the photos here of the 19th and 20th arrondisements. In many cases the materials in these new quarters are of low quality and age poorly. In the 20th arrondisement a building dating from the 1990s suffered from balconies falling off. In the 15th arrondisement there is the Front de Seine, a pet project of President Pompidou who thrilled at the idea of building a mini-Manhattan in central Paris. Today it is so dilapidated that barely thirty years after its construction it is in urgent need of a total overhaul. There is no patina there. Norma Evenson wrote a fine analysis of this misguided urban planning in her book Paris: A Century of Change, 1878-1978, (chapter 5) where she describes the demolition and rebuilding of Rue Nationale in the 13th arrondisement. Walk this street today and witness the deadness all around. The old neighborhood was poor, sure, but at least it had a there there. The street was alive with cafes, butcher shops, bakeries, grocery stores, etc., and provided a social glue bringing people together to create a vitality, a sense of place, and that thing so talked about today – community. Walk down Rue Nationale today. The street is lined with blank facades set back from the street, and a heavy pall settles over everything. Where there use to be 48 cafes on the street, today there is one. Speaking of the greatness of Paris Victor Hugo wrote, “This city does not belong to a people but to peoples . . . the human race has a right to Paris.”** I concur wholeheartedly. And the French would agree. And that is why I hold Paris to a higher standard. They want to be seen as the most beautiful city in the world, then act like it. It is stunning to think that a culture with such a history of spectacular architecture and streetscapes can suffer a complete aesthetic collapse as if a state of collective amnesia has fallen over the population of urbanists and architects who design the city. Of course the reasons are many and complex. One can go to the roots of Modernism, to the grand aspirations of those who forged the way, we can look at budgets, endless code constraints and much more. But despite all the reasons about the why of a building, in the end the building must stand on its own with no justification of any kind. And what we are left with is the feeling that the structure elicits from us. Feeling. That’s a dirty word in architectural circles but that’s where the rubber meets the road and that is the one thing that is not factored into the equation here. What do we feel standing before the building, inside the building or in the new street? Does it invigorate us, excite us, stimulate our senses? Or do we feel a flatness, a boredom and emptiness, an existential ho-hum that leaves us scratching our heads wondering, “What were they thinking? I’ve been in buildings and on streets where I feel my spirit soar, others that feel so delicious I could eat them with a spoon. Surface and texture are important. Some surfaces are alive, present. They speak. Other surfaces are vacant, dead. Some people, in defense of these depravities will argue that the buildings they replaced were uninhabitable, insalubrious. This may be true in some cases but certainly not all. Paris has a long history of developers and urban planners not hesitating to tear down a building that is perfectly restorable in order to build something larger with more apartments in order to increase their bottom line. The mantra, “It’s cheaper to tear down and rebuild than it is to restore” is universal. But let us imagine that the old buildings were uninhabitable. Why then is it seemingly impossible to design buildings that are interesting, compelling in their beauty, buildings that are pleasant to look or simply make us feel good? Why do we see an endless array of buildings without character, brutal in their obedience to a rationality that does not take into account the fact that humans will inhabit them? One of the most depressing features of new building in Paris is that where there were shops, today there are only blank facades. If Paris is recognized as one of the great walking cities of the world it is because at eye level every building has a shop, boutique, or some type of commerce to engage us. Everything is visually interesting. New buildings with their blank facades rob us of this pleasure and plunge us into an urban anesthesia. One example in the center of Paris is at 35 Rue Mazarine near Métro Odéon. See photo – 6th arrondisement. At first blush we see a building that resembles all the other 18th century building on the street. Actually it dates from 1997. I walked by the day after the original building had been torn down and found a gaping hole. A neighbor on the street was aghast. The new building is consistent with the neighborhood in its overall design except that there is no commerce on the ground floor. At the street level all we have is a door to the luxury apartments upstairs plus a large door leading to the underground garage. There is no other building in the quarter with a blank facade such as this. It’s as if part of the street has been rendered inert. Another example in the 4th arrondisement is on Rue Ave Maria. Anyone interested in seeing Paris’s most recent approach to these issues should take the Métro to Tolbiac in the 13th arrondisement and go for a stroll. A whole new quarter has been built from scratch around the new national library – Bibliotheque Nationale – a pet project of President Mitterand, opened in 1996. There has been much heated discussion about this library. Its four towers are designed to resemble open books. The architect, Dominique Perrault, failed to take into account the fact that walls of glass windows are destructive to books – light! – and after a grand opening with much pomp and circumstance, a hasty plan was put in place to provide for curtains to protect the library’s treasures. Some people have spoken with praise for the operation of the library, etc, once the bugs were worked out. Fine. But it is the exterior that counts. A building dialogues with a city through its exterior. It is the exterior that adds to or subtracts from our positive feeling of being in Paris. From the west side of the library one must mount an inhospitable, wooden staircase. One would do well to be in preparation for a triathalon. Not to speak of the trek up this staircase, in wet, slippery weather it is plain hazardous. Were people ever part of this equation? I come back to “feeling.” Walk around the neighborhood and see what it feels like. Tolbiac does not make the mistake of endless blank facades on the new buildings, indeed there are shops, etc. But the emptiness in the cookie cutter design is disheartening. Please do not mistake these thoughts and think that I am against change. I would have voiced no displeasure at the turn of the century, the 20th century that is, when Art Nouveau came on the scene, or later when Art Moderne, also known as Art Deco, appeared. Buildings in these styles are some of the most beautiful in Paris. Is it too much to demand that new buildings be as pleasing? If you want to rankle an architect today mention the word embellishment. Short of eliciting outright laughter you’ll get a wry smile or perhaps only a blank look. For thousands of years periods of architecture were defined largely by different styles of embellishment. Then post-World War II arrived and it all disappeared. Clean unadorned surfaces have dominated since. Modernism has evolved into post-modern, and neo-modern, yet everything remains clean of embellishment. How unfortunate. I believe the eye loves to savor detail and nuance. I’m a big fan of Louis Sullivan, Charles Rennie Macintosh, Julia Morgan, Hundertwasser, Gaudi, Frank Lloyd Wright. Even Austrian architect Alfred Loos who railed against embellishment and wrote a famous work, Embellishment is Crime, is a favorite. His surfaces are flat but full of decoration nevertheless. Architectural icon Le Corbusier was clear in his contempt for embellishment and showed it in his “machines for living” concept of architectural design and urban planning. His uber-rationalist approach lead to his famous Plan Voisin that called for the demolition of much of Paris’s Right Bank, including the Marais, full of what he called “meaningless buildings.” In its place he wanted to erect a grid of skyscrapers. Submitted to public viewing in 1925 at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, this madman’s approach to urban renewal was rejected by the French. My prediction is that some day in the future a young, radical architect will come along and upset the apple cart with the idea of reintroducing embellishment. Architects will deride but the public will adore. p.s. The issues presented here are being played out, as we speak, in the 11th arrondisement in Paris. At 154 Rue Oberkampf in the Menilmontant quarter, a most charming 19th century cobblestoned passageway, La Cité Durmar, lined on both sides with one and two story ateliers is struggling for its life. Charm is not wanting, another word that will likely elicit a wry smile from your local architect. The cobblestones in the passageway come from the Bastille and are classed of historic value and worth saving. Paris once had many of these sites but they’ve been gobbled up by developer’s wet dreams. One of the most beautiful, Cour du Dragon (Courtyard of the Dragon) built in 1715, was torn down in stages from 1926 to 1958. See 6th arrondisement Rue de Rennes before and after. I visited Cité Durmar in October, 2007. In one photo here a behemoth apartment complex in the distance shows the type of construction that will go on this spot if the passage is razed. Mayor Delanoe has done much to make Paris more habitable. I am told he wants to be remembered as one who respects “La Patrimoine,” French heritage. What better place to show his sincerity than here. He has already reversed an old trend of cutting back sidewalks in order to widen streets so as to adapt the city to the automobile by widening sidewalks, narrowing streets and adding bike lanes. His Velib project, placing thousands of bicycles around Paris for practically free use has been most successful. Now he would do well to bring his weight on the side of the little guy in this David and Goliath scenario. To see for yourself go to Google Earth. Enter the address 154 Rue Oberkampf, Paris, France, and fly over for a look. Hit the button for Roads and the name Cite Durmar will come up. I photographed the handbill on the large door to the passageway. The first line reads “We, the occupants of la Cité Durmar need help to make known the danger we face.” If the developers win and Cité Durmar is lost we can imagine the long list of reasons trotted out to justify the project. They will all make sense. And in that case the passing of Cité Durmar will go into the book I promise to write some day, When Terrible Things Are Done for Good Reasons. Save Cité Durmar! Note: The only photos here that are not mine are the Suburb of Nanterre the Campus of Jussieu and two of the three Durmar photos. To see more on Cité Durmar go to the French site www dot jardinsenville dot com. The Nanterre photo appeared in a magazine. I do not know the photographer. It is so illustrative of my point that I had to include it and can only hope that the photographer would not mind. Jussieu is a postcard too good to pass up. The others I shot as I flew about the city and cannot always give exact locations besides the arrondisement. *In 1961 a small group of Parisians passionate about the preservation of their city discovered a beautiful 17th century ceiling hidden behind a false 19th century plaster ceiling in the Hotel de Vigny on Rue du Port Royal. One of the group, Michel Raude, had the idea of putting on a concert of classical music in the mansion to show off the discovery to the public. The success of this event led to the creation of the Festival du Marais, a world class festival of theatre, dance and music taking place in the old mansions of the Marais. People who had shunned the quarter came back in great numbers and delighted in their rediscovery for this forgotten quarter. The festival’s success brought the press and high marks went not only to the performances but also to the architectural heritage on the brink of destruction. André Malraux, Minister of Culture, stepped in and in a landmark move created the Malraux Law declaring the Marais a Safeguarded Secteur thus prohibiting all demolition in the quarter. Incentives were put in place for property owners to renovate their buildings and bring them back to their original glory. This was a first. Individual buildings had been classed as historic monuments but never before an entire quarter. Not only the architectural gems were recognized for their value but also the more modest buildings in the quarter that together made up a new concept of “urban fabric.” **Quote taken from Norma Evenson. |

|

';

} else { print ' '; }

?> '; }

?>

Click here to see more of the Ugly Paris Buildings gallery.   6 Rue Beautreillis.  Rue Elzévir.  Rue Beaubourg at Rue Saint-Merri.   19th arrondisement Orgues de Flandre.  19th arrondisement Orgues de Flandre.  35 Rue Mazarine.  Rue Ave Maria in the 1940s.  Rue Ave Maria today. Same view.  Rue Geoffroy l'Asnier in the 1940s.  Same view today.   Le Corbusier's Plan Voisin - 1925.  Cour du Dragon on Rue de Rennes, circa 1900.  The Monoprix now stands in place of Cour du Dragon. In the distance, Boulevard Saint-Germain.   Cité Durmar.  Cité Durmar.  Cité Durmar.  Cité Durmar.  Cité Durmar.  Cité Durmar. |

|

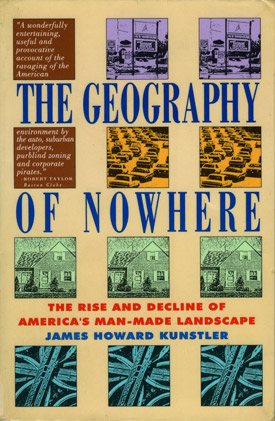

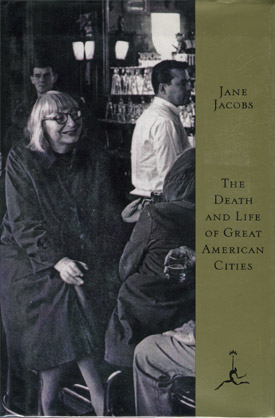

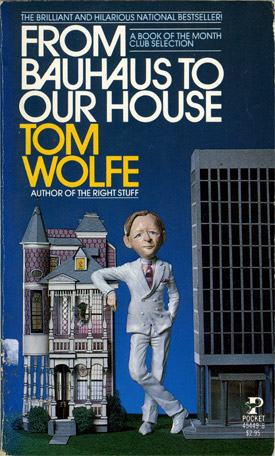

Required Reading The Geography of Nowhere by James Howard Kunstler is a most trenchant critique of the American urban landscape. Like Bob Dylan in the 1960s, Kunstler tells us what we already know but with a clarity and detail that helps us formulate our own thoughts and feelings. Tobacco manufacturers, not subject to the romance of their own advertising, refer to cigarettes as "nicotine delivery systems." How poetic. How real. Similarly Kunstler details how America, in all its modern permutations, has been turned into a delivery system for the personal automobile and the death of mass transit. His section on Robert Moses is enough to raise anyone's ire. His dissection of the transformation of his hometown Saratoga Springs, New York is a case study in what not to do and should be taught in every school of urban planning in the US.  Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities is a classic. As Rachel Carson's Silent Spring launched a generation into the environmental movement, this book galvanized throngs to protest the destructiveness of Robert Moses and his Adoration of the Auti (plural for auto). The impact of Jacobs' work rippled into large numbers of people marching in the streets of New York to stop Moses from carving up Lower Manhattan with a proposed expressway through The Village, Washington Square, etc. This was the first battle in his decades long career that he lost and he was not pleased.  Tom Wolfe's From Bauhaus To Our House is so brilliant that one wonders, "Didn't this stop everyone in their tracks and get them to rethink everything?" Hmm . . . guess not.  From A Cause To A Style by Nathan Glazer is a bit academic in style but most worthy in gaining an understanding of the process that begat The Great Bamboozle of modern architecture. He spells out its European origins, its evolution from the idealism of social reform, to its eventual dissolution into a celebration of the individual and the cult of personality.  John Silber's Architecture of The Absurd is a thoughtful and might I say heartfelt critique of contemporary architecture. His subtitle says it all, How "genius" disfigured a practical art. This could be a companion volume to the Glazer book.  See your local independent bookseller. |