|

During my trip to Paris in the fall of 2007 I began having strange sensations as I rushed around

the city. A pressure beginning in my chest reached down to my belly and up to my throat where I felt a slight burning sensation. Uh-oh. The discomfort disappeared

as soon I slowed down to a natural amble.

Once back home I went to the doctor, did a stress test, EKG, had dye injected inside me to take pictures of my heart, and guess what?

A blocked artery. And by blocked they meant 90% blocked. Dang!

So they scheduled me for an angiogram to take place one week later. There's no surgery involved, no incision. It's more of what I'd call a

procedure. A long wire is inserted up your femoral artery at the level of the groin. It's

similar to an IV. A tiny camera on the wire's end takes pictures and gives a complete picture of the cardiac situation.

From there they decide on the treatment. Either medication, a stent, or bypass surgery. My doctor thought it would be stent but

could not be sure without the angiogram.

While waiting for the week to go by the doctor gave me some nitroglycerin pills in case anything untowards were to happen while I was in

a state of rest. That's when things can get serious fast. If so, I was told, pop a pill and wait five minutes. If nothing improves,

pop another and wait five more minutes. If there's still no improvement, hmmm ... either pop another pill or call 9-1-1. Nah, that would never happen to me. That was on Friday, a week away from the actual procedure.

Then Tuesday morning rolled around. I was sitting at my desk thinking about the presentation I had lined up for the next day at the San Francisco Public Library where I was to do my Paris show and sign some books when suddenly that damn pressure in my chest came on like gangbusters! Damn, sitting down? It filled my whole chest from

side to side and from my belly up to my neck, along with lots of heat streaming up the side of my head to boot. So I pop

a nitro. No change. Damn! I pop another. Nothing. Groan ...

What to do? Pop another? Wait for it to go away? Maybe it'll worsen and blow me sky high. Reluctantly

I called 9-1-1. The thought of setting a huge machine into motion, not to mention having to cancel my library date, teed me off

royally. But I will say one thing, from that first phone call to my release three days later on Friday, I was in the hands of

extraordinarily competent and caring people. From the Berkeley Fire Dept, to all the EMTs, nurses, nurses aides and doctors,

I cannot say enough good about them and how grateful I am.

I called 9-1-1 "Hello, I think I'm having a heart attack." "Are you at 1542 Grant St.?"(how'd they know?) "Yes, I am." "We'll be there in a few minutes."

I put a couple of books in my briefcase, locked the door to my house and walked to the curb to wait their arrival. The Berkeley

Fire Department pulled up, sirens blaring, and two minutes later an ambulance. By then I was feeling better. Turns out that one of

the firemen is a guy I know from a café that I frequent. "Hey Mike, nice to see ya!" The EMT guys strap me to a gurney for a trip to

Kaiser Hospital and that was the beginning of many weirdnesses where you think, "I can't believe this is happening to me."

This being a Tuesday my scheduled Friday procedure got pushed up to Thursday. Wednesday was too booked. But instead of letting me go home they decided to

keep me around. After spending hours in ER waiting for a bed to free up, they strap me to the gurney again and begin moving me to a bed

in one of the wards upstairs.

We roll down the hallway, passing other people on gurneys in far worse condition than me, and head for the elevators. Then the

first big weirdness.

When my parents were ill I spent lots of time in hospitals and noticed that aside from the elevators

used by the public, there were other elevators not for public use that have an ominous feeling to them. The doors are dark with

large stenciled lettering that I have never taken the time to read but must be something like "These elevators reserved for

seriously ill and dead bodies only." So we wheel down the hallway, turn a corner, and there are those dreaded elevator doors in

front of me. Whoaaa!! I must be really sick! I'm in some deep shit now!

We get up to the ninth floor, to a room with 3 beds (damn), and once off the gurney they hand me the dreaded hospital gown. Me,

genius that I am, I put the damn thing on backwards, like a coat. Of course it should go on the other way. One of the

EMTs told me that this gown was invented by a German, Seymour Heiny. Mine was invented by the other Seymour, Seymour Dick. After

spending the better part of the rest of the day fiddling with the damn thing and finally figuring out my gaff, I grabbed another

one and put it on the other way so I was covered both ways. Success.

By then I'm hooked up to an IV, have oxygen in the nose, many wires to my chest to monitor heart activity and tell anyone who phones to stay away cause if they see me they'll think I'm near death.

So it's late Tuesday and I'm waiting for Thursday morning for the stent. And a helluva wait it was.

Basically it's like being on a very long, boring airplane ride but with no clothes on.

One weirdnesses was that if I had to use the bathroom I'd have to walk trailing that rolly thing with my IV bag hanging from it.

That was just too creepy so I laid in bed and peed in the damn plastic bottle. But

eventually they wanted to make sure I could walk so I had to get up and go for a stroll. Arghh!

Part of any great hospital is being poked all the time. Once they start they cannot stop. It goes on and on. And

how many times did they check my blood pressure? Dozens and dozens. The one thing that escapes me is that with all the care and

attention given, doctors and nurses do not understand the concept of quiet. It does not occur to them that when visiting a patient, that perhaps the other patient, the one who may be sleeping (you), would like some quiet. Any normal person would speak softly,

maybe even whisper. But not these folks. Everything is loud. And God forbid your room is across from the nurse's station, as was mine,

and they keep your door open, and boy can they get loud out there in the hallway.

The procedure itself was the "piece of cake" of the whole thing. At 5 am Thursday they strap me to the gurney again, wheel me

down the hall to that dreaded death elevator and put me into another ambulance for a half mile drive to Summit Hospital where

all Kaiser cardio work is done. Now wouldn't you think the ambulance would pull up under a canopy so you could go directly from the

hospital door into the ambulance? Nope. The ambulance parks in the middle of the parking lot about fifty feet from the

uncanopied door. They wheel me out in the cold, at 5 am, with only my hospital gown on. What would you do if it were raining? I ask. "Throw a tarp over you," was the reply. Now that's weird.

We arrive at Summit, and I must say that at first glance I was not reassured. It felt like a hospital in

Baghdad. Everything was shabby and disorganized. A woman lying on a gurney, gesticulating and swearing, (she must have been strapped

down) wore a black mesh mask covering her face. "Strange" I said. "Yeah, she's a spitter," said the EMT. Eeew! As we wheeled down the

hallways things got nicer in appearance and I was delivered into a big room with 10 curtained off bays that quickly filled with people all getting

something or other cardio. It felt like an auto repair shop.

My nurse at Summit, Patty, was the best. She prepped me, asked me the same questions other doctors and nurses had already asked

a hundred times, (do I have diabetes, any history of drug use, alcohol, allergic to shellfish) pokes me too, and after giving

me a valium, off I go. One is not out 100% but only semi-out. I really didn't feel anything remarkable, only a slight sensation

for a second of a wire running up my torso. I don't know if they spoke to me or not and the monitors the docs look at to see

what's going on were not at the perfect angle for me, although they did show me the thing afterwards but I was too out of it

to really get it. I'm going to ask for the DVD.

Once in the hospital bed after the stent I was told I was not to move one single whit for 6 hours. Uh-oh. That

doesn't sound good. Ok, you can move your feet and left leg, but your right leg, not a bit. And you can't lift your head

either. You are flat out still.

This is because the insertion point where they go into the artery is not sewn up but rather simply let to coagulate and get better

on its own. Any movement risks bursting the thing open. This doesn't look good at all. Once back in bed they put a heavy weight on the

point of insertion. It's strapped onto you and can be tightened to put pressure on the point as if you had your finger on a wound to

stop the bleeding. This weight must be in place for 2 hours. Once that's off you have four more hours of laying stock still. I was

still semi-out when they put the weight in place and also announced they were going to give me a catheter. This shocked me awake.

But hold it!! Here's the good news.

Someone figured it out. No more tubes stuck up anything. Now they have what is called a Condom Catheter. God bless whoever invented this

item. This is a rubber thing like a condom that is placed over the end of the pecker with a tube on the end. You pee and it goes right

into a receptacle under the bed. What could be easier! Brilliant!

When I met the doctor in the Summit prep room who was to perform my procedure he showed me his keychain with a stent encased

in acrylic. What a marvelous and beautiful little item. I definitely want to get one and will work on that. Do we dare think

of where we'd be without this modern marvel?

For the doctors doing a stent is as easy as changing a flat tire. One thing Western medicine has figured out to a T is the heart. Lucky us. Of course,

my procedure, compared to others of the cardio world was nothing. I've since met others with far worse

situations. One man had five stents. And how about those who've had bypass surgery? I pale in comparison. Nevertheless the

extraordinariness of it all leaves me awestruck.

And the one thing that impresses me most: While I had one artery almost totally blocked my body had grown a new artery to make

up the difference! A kind of auto-bypass. This is not unusual, I was told, in people who work out a lot, which I do. Working out

stimulates the body to grow. To think that my body has such a powerful urge towards optimal health that it will recreate itself

is amazing. Just think of where I would be if I simply got in line and co-operated with my body! And that's what I plan on doing

the best I can.

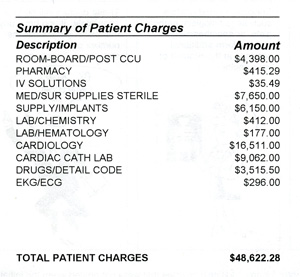

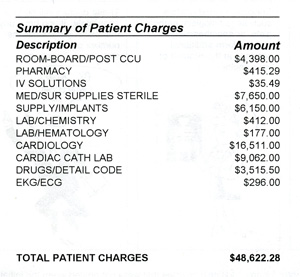

A few days after I got home I received an invoice in the mail showing me the cost of my one day at Summit Hospital. What might

that be? One friend thought as much as $2,000. Another went as high as 10 or $12,000. Well, fasten your seatbelt. The total -

$48,622.28. Best of all, the bill was itemized (see above). They actually have Room and Board on there. And that's a room shared with two other

men. Cost, $4,398. That's over $12,000 a day when the room is full. Gulp! The stent itself was $6,150. Oh, and the cost of that half

mile ambulance ride from Kaiser to Summit Hospital? $2067.23 What's wrong with this picture? Plenty. See Michael Moore's film Sicko.

Whatever criticism he may be due from whatever corner, the bottom line is that we must take the business out of healthcare.

Now for a brief rant!

The tragic reality of America's healthcare system could not be more starkly driven home than by the death on December 21, 2007

of seventeen year old Nataline Sarkisyan. In desperate need of a liver transplant, her insurer Cigna denied the request. The

reason? Too "experimental." This was not a doctor's decision but one of tidy, small minded bureaucrats who had no qualms about

handing out a death sentence in order to protect the company's bottom line. Even the surgical director of the Pediatric Liver

Transplant Program at UCLA Med Center where Nataline was hospitalized urged Cigna to reverse its decision.

Finally, after an onslaught of media pressure brought on by protest from The California Nurses Association, the National Nurses

Organizing Committee, plus a couple of hundred people demonstrating in front of Cigna's offices in Glendale, California, the

insurer reversed their decision. The news footage of the mother addressing the crowd is heartbreaking. Someone whispers in her

ear that Cigna has relented and ok'd the transplant and cheers go up all around. Minutes later news arrives that Nataline had

taken a turn for the worst. Within hours she was dead.

For the ultimate in black humor, unintended to be sure, dial this number late at night (1-818-500-6262) when

Cigna offices are closed and listen to their brief message. The tag line at the end is guaranteed to make one apoplectic.

For anyone wanting more information on this tragedy, which will surely be on-going as the family lawsuit proceeds against

Cigna, simply Google Nataline Sarkisyan.

For an informed opinion on healthcare in this county, and what should be done about it, go to the website for California Nurses

Association and do a search under Nataline's name.

By the way, Cigna's net income for 2006 was $1.2 billion. Full-year revenues were $16.5 billion. Their CEO is H. Edward

Hanway. Here's some promo on him at the company website.

"A past Chairman of the Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare, Hanway is a leader in the effort to improve

the quality, accessibility and affordability of health care in the United States. He is an outspoken advocate, at the

national level, for greater transparency in the health care quality and cost information available to consumers. He is

also a strong proponent of national quality standards for health care providers."

Have a nice day.

|

|

|